““A beautiful and moving portrait of a city that explains so much about our racial politics, then and now. Robenalt weaves together the stories of famous and not-so-famous black political leaders to show the consequences of racism and the ways that various leaders have tried to address it. An important topic that everyone would benefit from learning more about.” —Michael Smerconish, CNN host and Sirius XM radio journalist”

““Jim Robenalt’s Ballots and Bullets portrays a discrete but instructive chapter in American history. The lessons therein are relevant today. As I said many times in public office, those who know history must learn from it; those who don’t know the mistakes of history are bound to repeat them.””

Publishers Weekly

“Cleveland attorney Robenalt deconstructs the events leading to a violent 1968 confrontation between black nationalists and the Cleveland police that left three officers, three nationalists, and two civilians dead in this valuable history. Robenalt meticulously examines the larger forces that drove the 1960s black nationalism movement and the motivations and experiences of the individual black nationalists involved in the uprising. Particularly insightful are the discussions of the national debates among black people about how to improve the status of black Americans, specifically the contrast among the pacifist views of Martin Luther King, the more militant internationalist view of Malcolm X, and the even more militant view of other radical groups. Equally illuminating is Robenalt’s frank description of the inequities affecting Cleveland’s black population, which included high unemployment, a tattered relationship with the police, inadequate medical care, and animus directed at them by the city’s politicians’ and law enforcement, while one participant said, “It started over 200 years ago,” when asked why the militancy now. The moment-by-moment description of the firefight between police and black nationalists is chilling. Readers will find much to contemplate in this balanced report.”

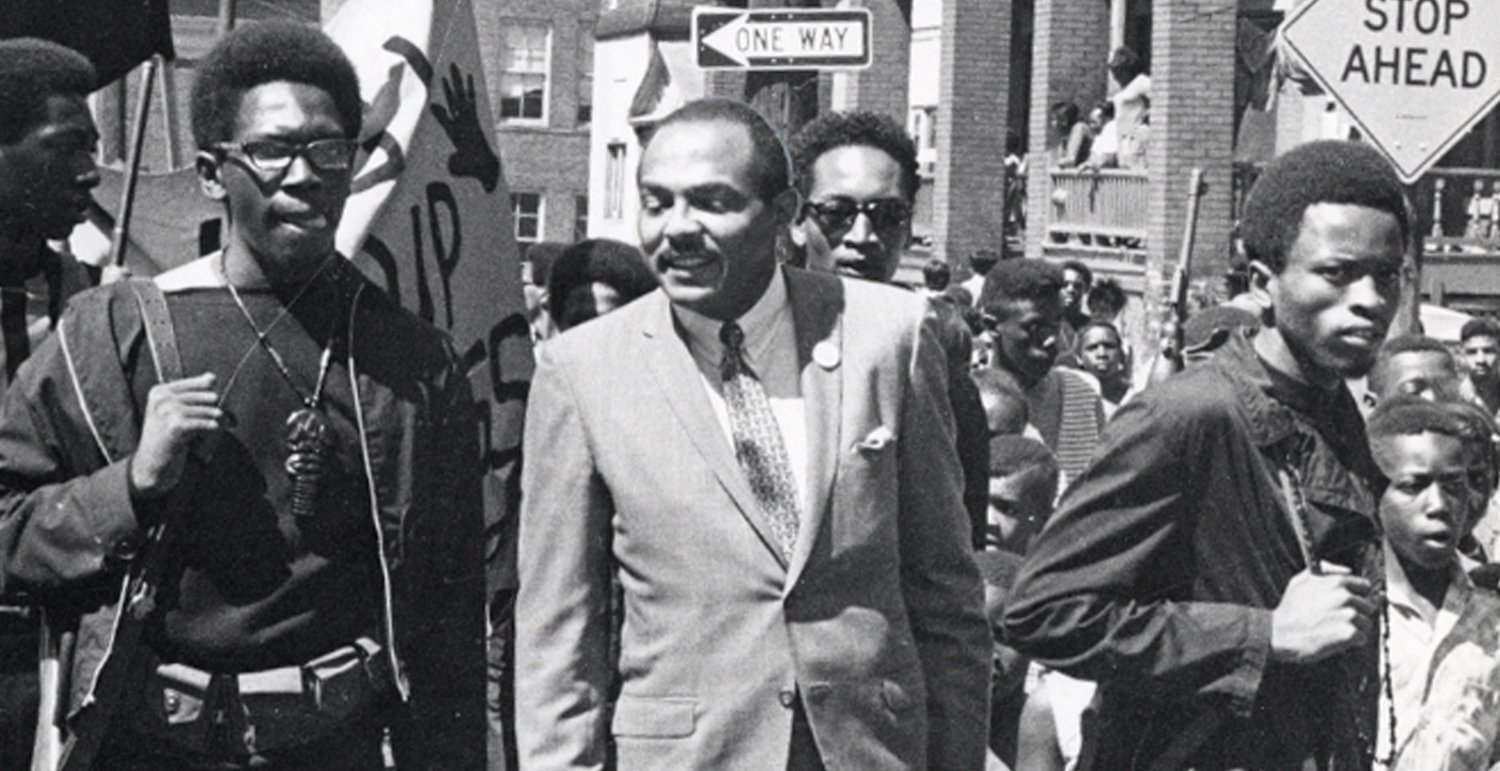

Cleveland Mayor Carl Stokes with former Browns player Walter Beach in the summer of 1968

Judge C. Ellen Connally, former President of Cuyahoga County Council

““In his reexamination of the events in Cleveland, Robenalt delves deeper than the deaths and resulting turmoil and looks at race relations, policing, black power and urban violence in America during the 1960s and specifically in Cleveland. The story is not just of urban violence in Cleveland but is a reexamination of the problems that faced the nation in the 1960s.””

For Judge Connally's entire review, click HERE

““Cuban revolutionary Che Guevarra is famously quoted for saying ‘one person’s terrorist is another person’s freedom fighter.’ That is the perspective that Robenalt takes as he looks at both sides of what happened on July 23, 1968 in Cleveland. Using newly discovered original sources, FBI records obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, court records and personal interviews, he brings a new perspective to the events leading up to the nights in question, the criminal prosecutions that followed and the racial politics of Cleveland.”

”

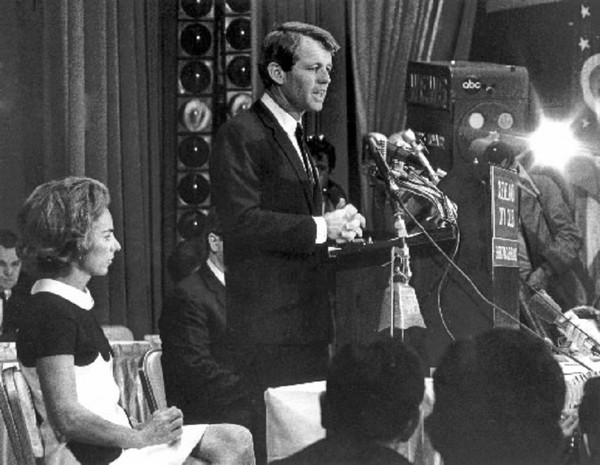

Fred "Ahmed" Evans and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. the day before Carl Stokes was elected as the first African American mayor of a major U.S. city. Dr. King came to Cleveland frequently in 1967 to assist in Stokes' election. He reached out to militants like Evans to try to widen his influence in northern cities where Malcolm X and his armed self-defense policy was better accepted.

“The book asks some hard questions, foremost among them that of why, fifty years later, the racial divide and the neglect of inner cities is still as bad, or worse, than it was in 1968? And why does police brutality, including the murder of unarmed black citizens, go unpunished?

“Racism in America has its own peculiar pathology,” writes Robenalt, citing how Americans are in denial about the degree to which it permeates the culture, politics, economics, justice system, and relationships at all levels of society.

“The heartbreak is that in 1968 we had made a start; we had taken a first step on honestly acknowledging our nation’s racial sickness, and we at least groped for solutions,” he writes, suggesting that massive investment in the nation’s inner cities and antipoverty programs, and enforcement of gun laws and strict regulation of gun ownership, might be good places to start anew.

“We cannot expect our police to solve the problems of poverty and racism. That is a job for all Americans,” Robenalt writes, calling on all to recognize their fellow citizens as brothers and sisters and act accordingly.”